Hugh Hefner, the iconic but morally questionable pioneer of the Playboy empire, has died.

Hef’s aesthetic was limited and the ‘bunny lifestyle’ he propagated probably played a not insignificant role in the growth of Trump-esque, mediocre men since at least the 1980s.

Nevertheless, his death provides a good opportunity to talk about the porn businesses. In particular, why isn’t there an Australian Hugh Hefner?

The answer: because Australia has some of the strictest censorship laws regarding sex in the Western world.

What!? I hear you yell. The laid-back nation of the fair go, cold beer and coward punches is also run by censorious prudes?!

Yep, and the current legal landscape doesn’t just impact the masturbatory aid business:* it also has major consequences for artistic expression in Australia.

*Full disclosure: I work for the masturbatory aid business.

Aussie Censorship 101

Cast your mind back before you torrented movies over the internet, and you will remember the classification system.

Films in Australia are classified as either G, PG, M, MA15+, R18+ or X18+. ‘Publications’ are also either classified as unrestricted, Category 1 (restricted) and Category 2 (restricted) (side note: labia are now allowed in nudie pics hoorah!).

Who does this classification?

The Australian Classification Board.

Who are they?

These people.

Why is this censorship?

Anything Refused Classification cannot be sold or publicly exhibited in Australia.

Most films depicting real sex (with some exceptions) will either be classified X18+ or Refused Classification entirely.

Sexy films will be granted X18+ status as long as things are kept relatively vanilla and there are no “depictions which purposefully demean anyone” whatever that means.

Kink is out, with the Classification guidelines on X18+ explicitly saying:

Fetishes such as body piercing, application of substances such as candle wax, ‘golden showers’, bondage, spanking or fisting are not permitted.

No fun.

Well films can still get classified as X18+ you porn obsessed weirdo!

Here is where things get complicated.

Even if a film is classified as X18+ the laws in every state in Australia bar you from producing, selling or publicly showing X18+ material or risk hefty fines.

But wait, I’ve seen X18+ material sold at [name redacted] store?

Luckily, censors have better things to do than raid adult stores (although raids do indeed happen).

Wait, you just said ‘States’ does that mean it is legal to produce, sell or publicly show in the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory?

It is complicated, but kinda.

In the ACT you need to obtain a (bloody expensive) X-rated license to produce, sell or publicly exhibit. In the Northern Territory, things are very heavily regulated (for example, you can only sell X-rated material ‘upon request’) and heavy fines are attached to non-compliance.

Who buys DVDs anymore? Why not just upload things to the internet?

That’s what most porn producers do! But the Australian censor extends online as well.

The eSafety Commissioner is the central agency for regulating internet content in Australia. It works under a complaints based system.

In response to a complaint, the Commissioner will ask an Australian based internet service provider to take down any content that could be classified as X18+ or Refused Classification. In-fact, content that may be classifiable as R18+ can also be taken down.

Wait a minute I was casually researching this topic on PornHub and there is totally Australian based pornography out there!

Yep. Adult media producers in Australia either have to fly performers overseas for a shoot, pay an expensive licensing fee in the ACT or operate illegally.

Websites are hosted on US-based servers and everything from here on out gets real complicated (Join Eros for more info).

So there you have it, Australia’s weirdly censorious classification laws.

But Why Should I Care?

I’m sure many of you find the above laws very silly, but can’t get too riled up about the refused sale of ‘Big Titties 9: Now with Extra Boobage’.

Firstly, you are likely coming from a very narrow perspective of what pornography is, or could be.

Censorship laws in many countries have severely limited the kind of pornography that can be produced. The result: the market has been dominated by a cliché, Californian oeuvre that tends to reflect childish American perspectives on human sexuality.

Australian pornographers are kind of artsy, with interesting takes on erotica. Problem is: this fresh take on porn isn’t given an opportunity to flourish.

Secondly, limitations on depictions of real sex severely limit the sale and public exhibition of bona fide pieces of art in Australia.

Our classification regime has barred works by queer pioneers like Bruce LaBruce and Greg Araki. It has also made Australia an international joke by banning or censoring award winning films like Ken Park, Pink Flamingos and Baise-moi.

Finally, you should be pissed that a group of random people is telling you what you can and cannot watch.

Our country has national debates defending that right to racially vilify people, but nobody seems to care that grown adults cannot buy a film showing other consenting grown adults going at it.

Censoring sexuality hits on some pretty fundamental rights and liberties that are worth defending.

If there is ever a cause worth flying the free speech flag over: this is it.

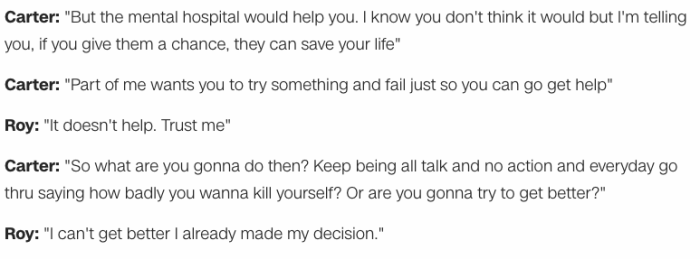

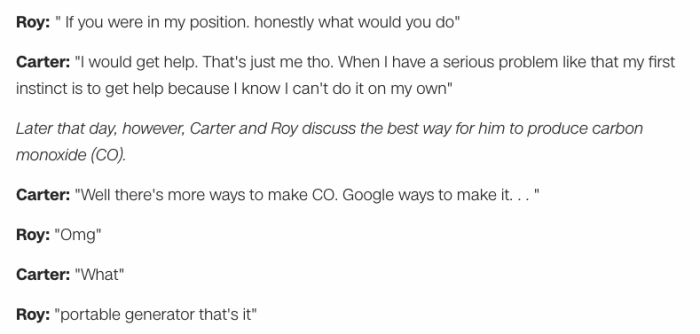

This raises complex questions about who is ultimately responsible for Roy’s death. After all, Roy appeared determined to commit suicide and refused to seek help. Carter initially attempts to help Roy, but is then co-opted into his plan for suicide and takes on the role of instigator.

This raises complex questions about who is ultimately responsible for Roy’s death. After all, Roy appeared determined to commit suicide and refused to seek help. Carter initially attempts to help Roy, but is then co-opted into his plan for suicide and takes on the role of instigator.